(Radio transcript, AM 1220 KHTS, airdate 2/15/07.

You can listen to it

here (mp3 file).

My segment starts 40 minutes into the one-hour program.)

Paul Strickland: Well, hello, and welcome back. This is "Thursday Matinee" and I'm Paul Strickland, your host on your hometown station AM 1220 KHTS.

Well my guest today is David Wisehart. Now let me tell you how I met David. You know, we have this wonderful college up here called the College of the Canyons and they have so many programs that they offer. And one of the things they do, they actually allow community involvement in some of their plays, along with the students on campus, and they perform them at the Performing Arts Center and also at the Black Box Theatre, which is really a state-of-the-art black box theatre. If you have never been there, you should really go and see something performed there.

Anyway, I actually was trying out for something over there and I met this man who actually has written, believe it or not — this is just amazing to me — a play in verse. And the play is 82 pages long and it's all in verse, from the period of Italy in 1502. I mean, it's just amazing. And not only is it in verse, but it's also written in the language and the thoughts of its time. It's amazing, David. How could you ever do this?

David Wisehart: Hi, Paul. Thank you.

Well, it took about three years to write. And, you know, I did a lot of research, I had actually recently left a job. I was working in Hollywood, and was working as a Producer in interactive entertainment and videogames, had saved up some money, and I had always wanted to be a writer. And I had always written on the side, but I want to write professionally, I wanted to devote my life to it. That was my passion.

I left the corporate world, left Hollywood, spent basically three years living off my savings, traveled to Italy, read most of Shakespeare, read a lot of Italian stuff, studied Italian, read Machiavelli — this play is based on a story from Machiavelli — and basically, you know, just immersed myself in that world, and came up with a language that I thought would fit the time and the period and the play I wanted to write.

PS: In verse.

DW: In verse, yeah.

Actually, the verse form is ottava rima. It's a verse form that comes out of Renaissance Italy and before that from the troubadour tradition in Provencal France, in the Occitan language. And Giovanni Boccaccio, who was an Italian poet, popularized it in Italy. At the time that I'm writing the play, which is 1502 — that's sort of the height of the Italian Renaissance — it was one of the more popular forms, along with the Petrarchan sonnet.

One of my characters is Lucrezia Borgia. The story is about the Borgia family. Lucrezia, after the events in the play, went on to become a patron of the arts in Ferrara, and one of the people that she patronized was Ludovico Ariosto, who wrote a long epic, Italian epic, in ottava rima, which in part talked about Lucrezia Borgia. But the whole thing was written in this verse form that I was reading at the time, and got really sort of sucked into it, and hooked into it, and I thought, "Wow, this is really great." And it's a way to do a verse play that's not faux Shakespeare, that's not Elizabethan, but has that heightened language, has the feel of the Italian Renaissance.

In verse, I think the form sort of influences, in some ways, the thoughts. I think if you write in Elizabethan you sort of think in that sense. If you write in prose, you think more like a common man. The form sort of dictates, to some extent, or influences, the kinds of things you write about. And this is written in rhyme, its written — in English — the iambic pentameter line.

PS: Now let me ask you this, David. That's really a great explanation, and I want to go back to that, but I want to ask you, now is this the first time this is being performed?

DW: At C.O.C. It is the first time. It'll be performed for the New Works Festival. It will be performed in March. The dates, the general dates, are March 22-25. There will be a number of plays. It's eight plays. This will be one of them. It will not be performed in it's entirety, but several scenes. This is a full-length play. The other plays are short plays. Probably two separate evenings. We're still working out the schedule, but the dates are the 22nd through the 25th in the Black Box Theatre at the C.O.C., which is where we're going to be rehearsing and working on it.

PS: Will it be in the evening or in the afternoon?

DW: I believe there will be evening and matinees. It's Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday. I believe the weekends will have matinees as well. The exact schedule is yet to be determined, but those are the days.

PS: Well, I know that the first Thursday in the month, what I call "C.O.C. Day," I have people come over from there and they tell me what's coming up, so they'll tell us, I'm sure, about this. So this is very, very, very interesting. And so you will get to see your own play. It must be a quite a feeling.

DW: It's very exciting. I wrote this very much in a vacuum. You know, had sent it out. When I finished — it took about three years to write, like I said — I sent it out to a number of the major regional theaters around the country, and nobody was interested in reading it. And then I saw a C.O.C. bulletin about how the New Works Festival was for the first time opening itself up to the community, and not just to the college — I was not a C.O.C. student at the time — and I thought, well, this'll be a great chance to hear actors actually perform it, and I submitted it, got it accepted, and I've had a chance now to hear some of the student actors both audition on it, and in the Winter Session actually repeat the lines. I had done some readings for family and friends, and I kind of had it in my head, but to actually hear real actors, trained actors, speak the lines, is just absolutely amazing.

PS: That was my next question. I know it's one thing to write something, and then to actually hear or see it being performed, or both. Just to hear their version, their interpretation, that doesn't always gel with yours, does it?

DW: Well, so far we've done mostly cold readings. They haven't had a chance to really deeply rehearse it. It doesn't exactly match what's in my head, but that's also the nature of theater. It's a collaborative art. The actors bring their own sensibility to it. They bring their own physicality, they bring their own voice, they bring their own conception of what the play is about, and the director obviously has an influence on that as well, in terms of the pace, what to emphasize —

PS: Well, he's the one that actually brings the two together, the director.

DW: Yes, yes.

PS: And I know that must be exciting for you, to be involved in all of that.

DW: It's incredibly exciting. And sort of sitting back and watching that, and stepping away from it and seeing other people take it over. It's actually very thrilling.

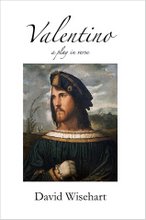

PS: We forgot to mention the name of your play. It's

Valentino. This is a play in verse. We're talking with David Wisehart. And we're going to hear even more from him. And we'll be right back on your hometown station, AM 1220 KHTS.

— COMMERCIAL BREAK —

PS: Hey, we are right back on "Thursday Matinee," and I'm Paul Strickland, your host, and this is your hometown station AM 1220 KHTS. And we're visiting with David Wisehart, a playwright who has written a play,

Valentino: a play in verse.

He was telling us all about that kind of verse, and this is a play that will be performed for the first time at the New Works event over at the College of the Canyons Performing Arts Center. And that's coming up soon.

And

Valentino is something that David had written in verse and it takes place in Italy in 1502, and he actually took a verse form that was used around then, is that right?

DW: Yeah, it's the ottava rima verse form. Not that well known —

PS: What exactly is that verse form?

DW: What it is, is an eight-line stanza, iambic pentameter — so, if you're familiar with blank verse in Shakespeare, that's sort of the basics of it. It has an alternating rhyme scheme of a-b-a-b-a-b-c-c. So there's a couplet at the end. And what I do in the play is, you know, there are some monologues, some speeches —

PS: All with one character saying that.

DW: — where you'll have that, but in a lot of it I break it up into dialogue. So when you're listening to it in the theater, you will sort of lose the sense of it being in rhyme and pick up the sense of it being just the characters. And there is always that cadence underneath it, you've got always that iambic pentameter. It's like a heartbeat that runs throughout the entire show and sort of propels everything forward. And you've got the rhymes, and what the rhymes do for you is it builds anticipation and release. So if you're listening for it, you're sort of anticipating what that rhyme might be, but eventually you're going to lose that sense of it and they come as surprises.

PS: Listeners, when you hear this, it's just amazing. This is a man who gave up his job and took three years in writing this play. It's 82 pages. And it's just absolutely a beautiful piece of work here, and now you're going to get a chance to see this, locally, right here in Santa Clarita, for the first time, and for him it's the first time, too.

DW: Yeah, it's great.

PS: It's just amazing. And you know what I was thinking as you were talking, David, it just crossed my mind, that in 1502 there was absolutely zero technology, so all people had was the mind and thought and reading and thinking —

DW: Yeah, it was a very interesting time. The Renaissance was — everything was changing.

PS: Everything was changing at once. And the arts brought them through.

DW: Right. To give you a sense of the time, there are two relatively famous people who are characters in the play. The play is about the Borgia family —

PS: Leonardo —

DW: Leonardo da Vinci is a character. Leonardo had worked at this period designing war machines for Cesare Borgia, who is Duke Valentino. He was known as "Valentino." And he hired Leonardo da Vinci to draw maps, to build fortresses, and to build war machines, most of which probably weren't built, but the designs that we think about — flying machines, and those kind of things — came out of this period, when he was designing war machines. He was not actually painting much. He was doing a lot of anatomical studies because there was warfare. Valentino was, you know, killing a lot of people, so there were corpses laying around. He was, you know, doing dissections. But this was very sort of —

PS: Nothing like that happens today.

DW: No, no, no, no. But it is a very sort of volatile period in the Renaissance, and the Borgia family, they were the rulers of the Church. The interesting thing is, the father was the pope and he had children, and the children were trying to take over — Valentino was trying to take over Italy and carve out a duchy for himself, and he was sacking all these towns.

He is actually — and one of the things that drew me to it — if you're familiar Machiavelli, Machiavellianism, Machiavelli's

The Prince, the story comes out of that. Machiavelli was an envoy, a diplomat, for Florence to the court of Valentino, and he greatly admired Valentino. And what we think of as Machiavellianism, this sort of ruthless power politics —

PS: Not really, but it still works today.

DW: — comes not from Machiavelli himself, but the people that he observed and particularly from this character, Valentino. So he was both brilliant and treacherous. He spoke five languages. He wrote poetry. He was a patron of the arts. And he conquered a great deal of Italy, and everybody sort of admired him. He was tall, handsome, all these things. Everybody said, "Wow, this is a great guy." But he was also ruthless in a lot of ways, too. So he was very Machiavellian.

PS: But I think he was very aware of what people thought about him, so he used that.

DW: Oh, yes. That's a big part of it as well.

PS: You know what was so interesting, one of the interesting things with Machiavelli is to "befriend your enemies" so you always keep them at hand.

DW: Keep your enemies close. "Your friends close, and your enemies closer." Yes.

PS: That's something that I've never forgotten. And that still works. Many of the things he wrote about, you can use.

DW: Yeah, it's human nature. It's one version of how to look at human nature.

PS: Early psychology.

DW: Right. One of the things that got me interested in this was the

Godfather films. I was at UCLA in film school and had an entire class on the

Godfather films, and Francis Coppola stepped in and was talking about the making of the films. He was a guest, and he talked about how Mario Puzo had based the characters of the Corleones on the Borgia family, and I didn't really know who the Borgias were. And so I researched them and found they were sort of the proto-

Godfather family. They were sort of a crime family in the Renaissance. So there's a little bit of that kind of family dynamic that you see in a contemporary setting in

The Godfather, in a historical setting was these characters as well.

PS: Well that sounds like that sparked you on, right?

DW: That was a big spark. I was a big fan of the

Godfather films, and became more and more interested in that period, and —

PS: And you "went to the mattresses!" And you had so much fun. And now we can see this at the C.O.C. Performing Arts Center, right?

DW: Yes, at the New Works Festival in March. We're in rehearsals now. And we're just finishing up with final casting and really looking forward to the whole rehearsal process, and watching all the other plays as well.

PS: Oh, my gosh. Well, that's so exciting. David, you know, I'm so glad you came to visit with us. And I look forward to you coming back when we're very close to the show actually being performed, if you don't mind, then we can really renew people's interest and get more and more and more people over there to see you, David Wisehart. And David, I know that you'll be very successful.

DW: Thank you, Paul.

PS: We hope that this will just lead you to the stars.

DW: The first step, thank you.

PS: The first step. Thank you very much. And this is your hometown station AM 1220 KHTS.